Image Source: IOP Science

Scientists at Wake Forest University School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina reported using a neural implant to stimulate higher-level thinking in monkeys, providing the first demonstration in primates of the sort of brain prosthesis that could eventually help people with damage from dementia, strokes or other brain injuries. The study was published on Sept. 14 in IOP Publishing’s Journal of Neural Engineering.

According to the New York Times: “In the study, researchers at Wake Forest trained five rhesus monkeys to play a picture-matching game. The monkeys saw an image on a large screen — of a toy, a person, a mountain range — and tried to select the same image from a larger group of images that appeared on the same screen a little while later. The monkeys got a treat for every correct answer.

After two years of practice, the animals developed some mastery, getting about 75 percent of the easier matches correct and 40 percent of the harder ones, markedly better than chance guessing.

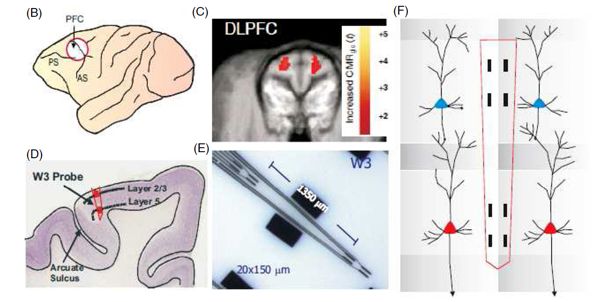

The monkeys were implanted with a tiny probe with two sensors; it was threaded through the forehead and into two neighboring layers of the cerebral cortex, the thin outer covering of the brain.

The two layers, called L-2/3 and L-5, are known to communicate with each other during decision making of the sort that the monkeys were doing when playing the matching game.

The device recorded the crackle of firing neurons during the animals’ choices and transmitted it to a computer. Researchers at U.S.C., led by Theodore Berger, analyzed this neural signal, and determined its pattern when the monkeys made correct choices.

To test the device, the team relayed this “correct” signal into the monkeys’ brains when they were in the middle of choosing a possible picture match, and it improved their performance by about 10 percent.

The researchers then impaired the monkeys’ performance deliberately, by dosing them with cocaine. Their scores promptly fell by 20 percent.

“But when you turn on the stimulator, they don’t make those errors; in fact, they do a little better than normal,” said Robert E. Hampson of Wake Forest, a study author.”